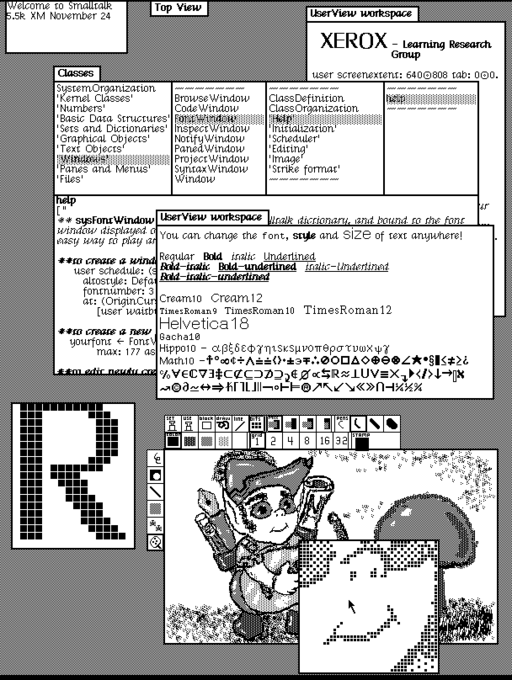

Take a look at this picture:

That's a photo of Smalltalk 76 running the prototypical desktop UI. It's taken for granted that this photo will be viewable for the indefinite future (or as long as we keep a PNG viewer around). But when we think about code, maybe the very same Smalltalk code we took this photo of, it's assumed that eventually that code will stop running. It'll stop working because of a mysterious force known as bit rot. Why? It's this truly inevitable? Or can we do better?

We can do better

Bit rot often manifests in the case where some software A relies on a certain

configured environment. Imagine A relies on a shared library B. As time

progresses, the shared library B can (and probably will) be updated

independently of A. Thus breaking A. But what if A could say it

explicitly depends on version X.Y.Z of B, or even better yet, the version

of the library that hashes to the value 0xBADCOFFEE. Then you break the

implicit dependency of a correctly configured environment. A stops

depending on the world being in a certain state. Instead, A

explicitly defines what the world it needs should look like.

Enter Nix

This is what Nix gives you. A way to explicitly define what a piece of software needs to build and run. Here's an example of the definition on how to build the GNU Hello program:

with (import <nixpkgs> {});

derivation {

name = "hello";

builder = "${bash}/bin/bash";

args = [ ./builder.sh ];

buildInputs = [ gnutar gzip gnumake gcc binutils-unwrapped coreutils gawk gnused gnugrep ];

src = ./hello-2.10.tar.gz;

system = builtins.currentSystem;

}

It's not necessary to explain this code in

detail.

It's enough to point out that buildInputs defines what the environment should

contain (i.e. it should contain gnutar, gzip, gnumake, etc.). And the

versions of these dependencies are defined by the current version of

<nixpkgs>. These dependencies can be further pinned (or locked in the

terminology of some languages like Javascript and Rust) to ensure that this

program will always be built with the same exact versions of its dependencies.

This extends to the runtime as well. This means you can run two different

programs that each rely on a different glibc. Or to bring it back to our

initial example, software A will always run because it will always use the

same exact shared library B.

A concrete example. This will never bit rot.

To continue our Smalltalk theme, here's a "Hello World" program that, barring a fundamental change in how Nix Flakes works, will work forever1 on an x86_64 linux machine.

The definition of our program, flake.nix

{

inputs.nixpkgs.url = "github:NixOS/nixpkgs/nixos-20.09";

outputs =

{ self, nixpkgs }:

let

pkgs = nixpkgs.legacyPackages.x86_64-linux;

in

{

defaultPackage.x86_64-linux = pkgs.writeScriptBin "hello-smalltalk" ''

${pkgs.gnu-smalltalk}/bin/gst <<< "Transcript show: 'Hello World!'."

'';

};

}

The pinned version of all our dependencies, flake.lock

{

"nodes": {

"nixpkgs": {

"locked": {

"lastModified": 1606669556,

"narHash": "sha256-9rlqZ5JwnA6nK04vKhV0s5ndepnWL5hpkaTV1b4ASvk=",

"owner": "NixOS",

"repo": "nixpkgs",

"rev": "ae47c79479a086e96e2977c61e538881913c0c08",

"type": "github"

},

"original": {

"owner": "NixOS",

"ref": "nixos-20.09",

"repo": "nixpkgs",

"type": "github"

}

},

"root": {

"inputs": {

"nixpkgs": "nixpkgs"

}

}

},

"root": "root",

"version": 7

}

copy those files into a directory and run it:

❯ nix run

Hello World!

Solid Foundations

With Nix, we can make steady forward progress. Without fear that our foundations will collapse under us like sand castles. Once we've built something in Nix we can be pretty sure it will work for our colleague or ourselves in 10 years. Nix is building a solid foundation that I can no longer live without.

If you haven't used Nix before, here's your call to action:

- Nix's homepage: https://nixos.org/

- Nix's Learning page: https://nixos.org/learn

- Learn Nix in little bite-sized pills: https://nixos.org/guides/nix-pills/

Disclaimer

There are various factors that lead to bit rot. Some are easier to solve than others. For the purpose of this post I'm only considering programs that are roughly self contained. For example, if a program relies on hitting a specific Google endpoint, the only way to use this program would be to emulate the whole Google stack or rely on that endpoint existing. Sometimes it's doable to emulate the external API, and sometimes it isn't. This post is specifically about cases where it is feasible to emulate the external API.

Footnotes

Okay forever is a really long time. And this will likely not run forever. But why? The easy reasons are: "Github is down", "A source tarball you need can't be fetched from the internet", "x86_64 processors can't be found or emulated". But what's a weird reason that this may fail in the future? It'll probably be hard to predict, but maybe something like: SHA256 has been broken and criminals and/or pranksters have published malicious packages that match a certain SHA256. So build tools that rely on a deterministic and hard to break hash algorithm like SHA256 (like what Nix does) will no longer be reliable. That would be a funny future. Send me your weird reasons: "marco+forever" ++ "@marcopolo.io"